Q&A: How agriculture can drive restoration

Canadian farmland is used to grow the crops and raise the livestock that feed us. It is essential. But much like in cities, land development has conventionally displaced wildlife habitats.

ALUS, a farmer- and rancher-led non-profit, offers farmers sustainable and nature-friendly project opportunities that facilitate habitat and ecological restoration on agricultural lands across the country.

And we’re helping to make this happen by supporting ALUS projects in five regions in Ontario and Quebec through our Nature and Climate Grant Program, presented in partnership with Aviva Canada.

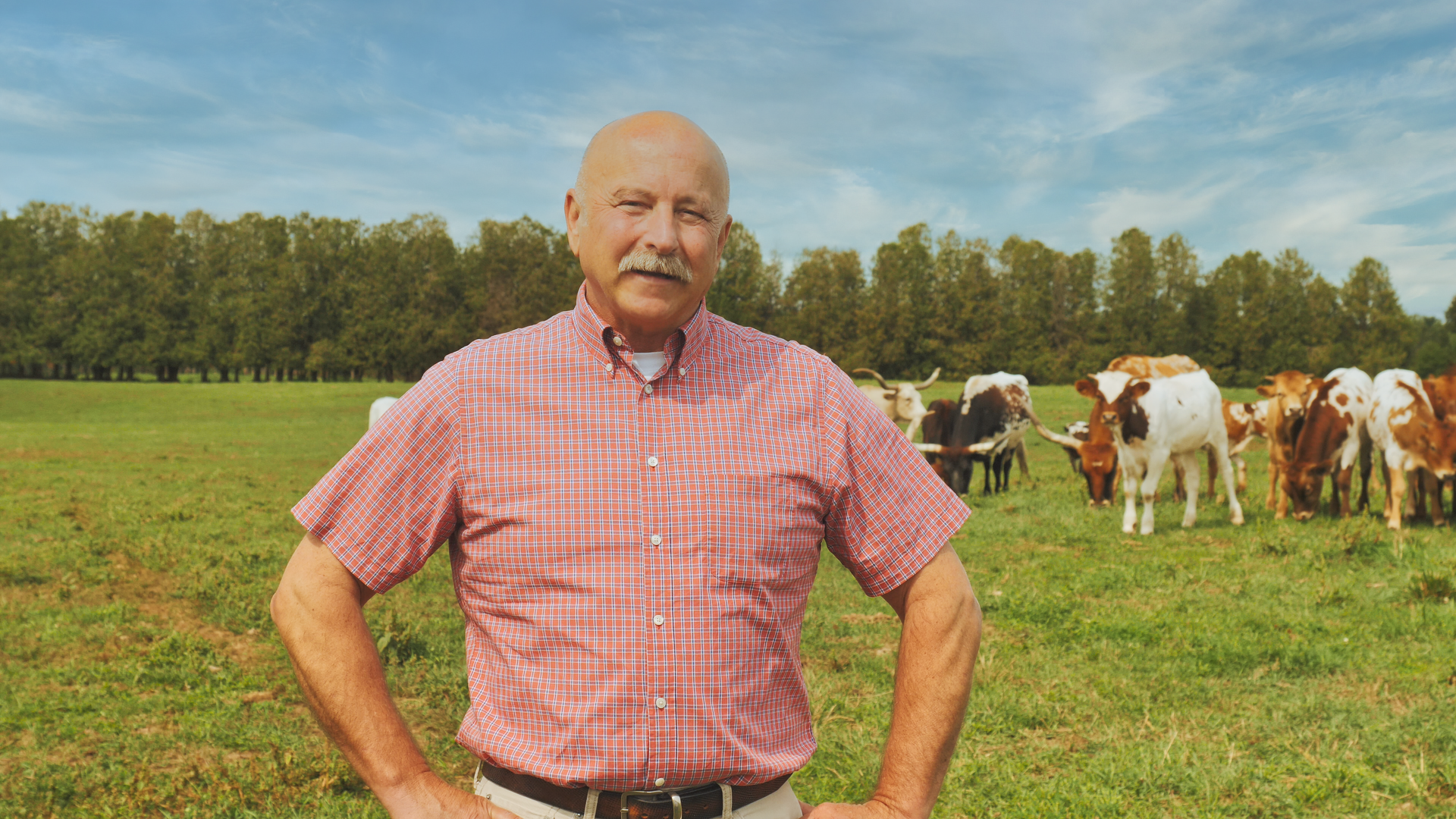

We spoke to ALUS CEO, Bryan Gilvesy — who operates a grass-fed beef farm in Tillsonburg, ON, and who has been involved with the organization since 2006, when he became the third-ever participant in the program — to understand how agriculture and nature can grow together.

How is ALUS engaging farmers in conservation efforts?

We focus on what we call the “multifunctional farm.” That’s the farm that produces ecosystem services, [which are benefits to humans from nature] in addition to food and fibre. It’s a matter of connected benefits. At its core, our work is about winning the hearts and minds of people on the land who haven’t been engaged before — and who have something to offer us in a conservation sense. Then they go off and create results, and then they grow the results. Solving environmental problems is a wonderful — and very purposeful — byproduct.

Can you give me an example?

One of the most extraordinary projects I’ve ever seen in our system was in Lambton County [ON]. There was an area of farmland that wasn’t the best because it was in a depression. So the landowners, working with ALUS Lambton, developed a series of about 10 connected wetlands, allowing water in each to settle and overflow into the next before going into the main drainage pipeline.

It created marvelous wetland sites, which brought back all kinds of biodiversity, and it also created a settling function that kept nutrients from going directly into the lake. And we did not in any way shape or form impede the drainage that farmers consider their lifeblood in that part of the country. It was a complicated project but to me, it was genius.

How does the work that ALUS supports affect biodiversity?

The biodiversity response to our work is almost instantaneous. It’s not the full suite right away — it starts with something simple, like insect life, then bird life follows, and it just builds.

On my own farm, we’ve restored some tallgrass prairie. We’ve attracted all kinds of insect life in response to that, which has attracted the bats — we have all eight of the bat species present in Ontario on our land. Then there are the endangered species. We’ve got badgers living here, and we have bobolink. By every dimension we’ve measured, everything is better. It’s just really cool.

Speaking of your own farm, how has being an ALUS participant changed you as a farmer?

It gave me a new definition of what my farm does, but more importantly, a new definition of what my role is. I now consider myself a steward who is needed to solve the world’s greatest problems. I like to think that every participant that walks in our door experiences that transformational moment. It’s like taking a seed and putting water on it.

Read More: Nature and Climate Grant Program

Sowing change: How Canadian farmers are addressing the biodiversity and climate crises

Act Locally: How to make your yard more nature-friendly with native shrubs

Act Locally: How to De-Pave Your Property

Restoring Utopia: How one group’s watershed work helps wildlife and hinders climate change

Meet 6 groups restoring biodiversity (and storing carbon) across the country