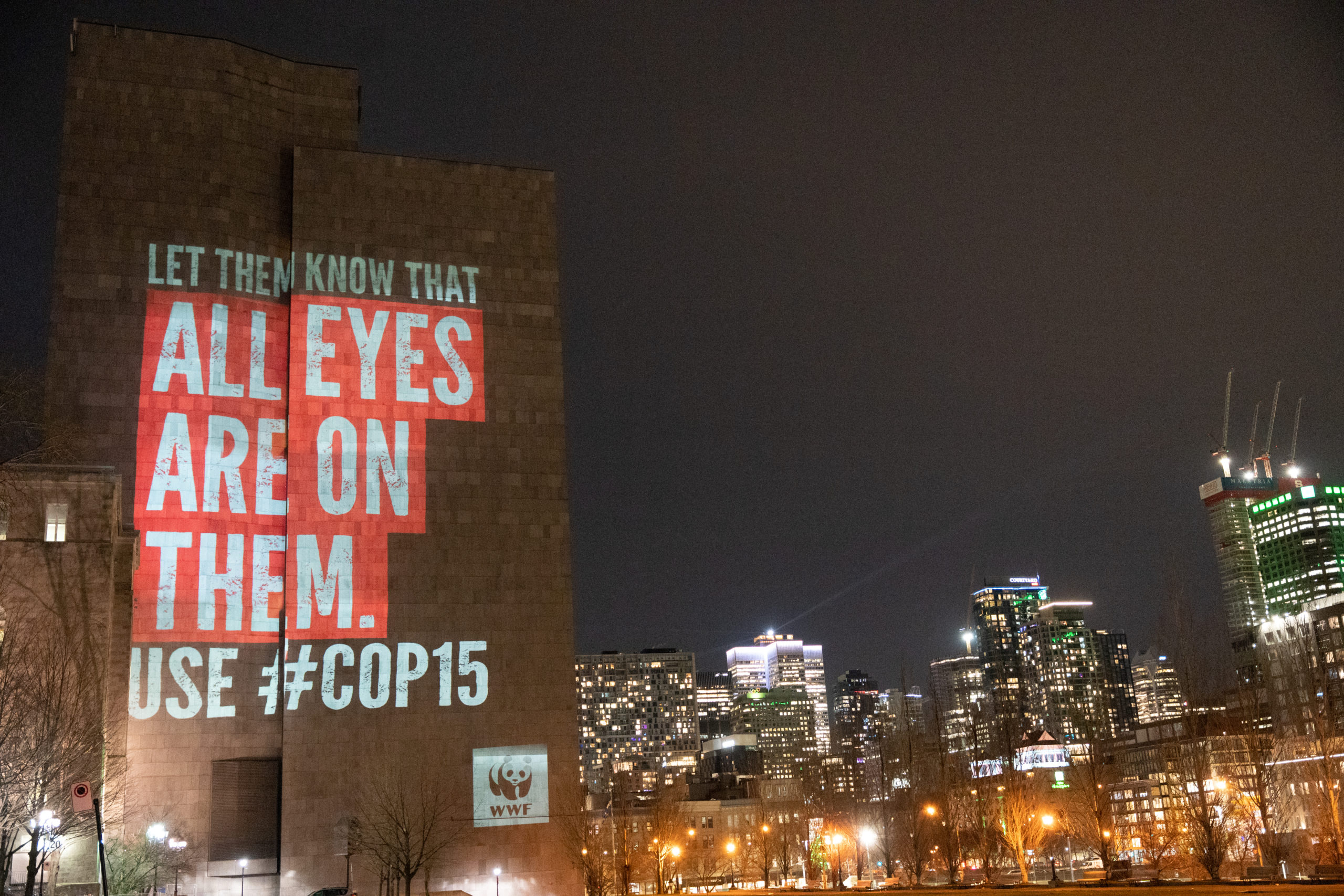

COP15: The world is watching. The clock is ticking. Wildlife is waiting

Around 17,000 delegates from nearly 200 countries, as well as NGOs like WWF — there are staff here from 30 offices around the world — have descended on Montreal’s Palais des Congrès for the UN biodiversity summit, COP15.

And we all share a vital goal: halt and reverse the accelerating destruction of nature and avoid the potential extinction of a million species. Plus, figure out how to pay for it while ensuring equity and effectiveness.

In case you were wondering how vital the goal is, UN Secretary-General, António Guterres hardly minced words in his opening address. “With our bottomless appetite for unchecked and unequal economic growth, humanity has become a weapon of mass extinction,” he warned. “This conference is about the urgent task of making peace.”

On that note, negotiators are aiming to craft an ambitious agreement (the Global Biodiversity Framework, or GBF) by nailing down 22 targets, like protecting 30 per cent of the planet by 2030.

But ambition is meaningless without enforceable monitoring and implementation mechanisms. After all, the last time this group hammered out a decade of nature protections — at the Aichi, Japan conference in 2010 — not a single target was fully met.

Another major difference at COP15 is a dramatically increased focus on Indigenous knowledge, leadership, and land and water rights, a point made clear from the jump when Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s opening speech was immediately interrupted by anti-colonial chants and drumming from Indigenous protestors.

“Hopefully, this is an era where we turn the page and allow Indigenous people to determine their future and let government just find a way to support it and move forward,” WWF-Canada’s lead Arctic specialist, Paul Okalik said a few days later, following our breakfast series panel on Indigenous-led conservation.

“Inuit, and our fellow Indigenous populations everywhere, need ongoing support. Let them lead instead of being told what to do all the time. We should be the ones that decide our own fate and make our own decisions,” he said, adding, “we’ve been doing this for quite some time, and we’ve done OK. It allowed us to move forward to this day and we’d like to keep going — and government should be supporting that effort.”

So far during the summit, Canada has been putting its money where its mouth is, beginning with the announcement of $350 million to support biodiversity efforts in developing countries.

That was followed by $800 million for four large-scale Indigenous-led conservation efforts covering almost a million square kilometres, include a Great Bear Sea project by 17 Coastal First Nations in BC; a vast Qikiqtani Inuit Association-led project in Nunavut; a boreal forest and freshwater project spanning the Northwest Territories, led by 30 Indigenous governments via Indigenous Leadership Initiative; and a Mushkegowuk Council project in northern Ontario to steward the Hudson and James Bay Lowlands, the world’s third-largest wetland and a globally significant carbon sink.

Canadian environment minister, Steven Guilbeault also announced the first 14 recipients of the Indigenous-led Natural Climate Solutions initiative, which WWF-Canada president and CEO, Megan Leslie called an important example of how to simultaneously support reconciliation, biodiversity and climate action.

“Accelerating the roll out of programs like this is exactly what we need if we’re going to achieve our ambitious goals,” Leslie said. “We look forward to seeing the lasting impacts of this National Indigenous Guardians Network, and hope to see it continue to grow.”

Meanwhile, the opening plenary session broke into various working groups, panels and side events to debate agenda items, goals and targets. But by the weekend, negotiators had only reached consensus on three targets out of 22, raising concerns that politics threated to take over.

As each country’s environment ministers arrive later this week for the high-level segment to finalize the framework, it might behoove them to remember the words of Pakistani youth activist Aisha Siddiqa at WWF’s daily press conference last Friday.

“I don’t know how many years, how many panels, how many conferences it’s going to take to realize this. But there will come a time, and it’s very close, where you will not be able to negotiate with nature. Because the thing about nature is it is powerful; more powerful than all of us.”

What’s coming for COP15 week 2

While some progress has been made toward a rights-based agreement, including new discussions over the right to a healthy environment, there’s still a long way to go in this final stretch to arrive at an ambitious transformative and measurable framework.

WWF staff sitting in on the negotiations say it’s still looking like countries will commit to conserving at least 30 per cent of the planet, safeguarding the rights of Indigenous peoples and local communities, and resource mobilization to finance conservation in developing regions.

Environment ministers from each country will be arriving mid-week to finalize the framework, but a lot of text remains in flux and alarm bells are ringing. We’ll be watching how countries plan to implement the framework — the part of the negotiation that will ensure that the targets are met as we approach 2030 — and any attempts to water down or delay.

“Negotiators have, for the most part, focused on minutia rather than the big-ticket items where compromise must be forged if the world is to secure an ambitious global biodiversity agreement in Montreal. They have left themselves a lot to do in the next few days,” warned Li Lin, WWF International’s senior director of policy and advocacy.

“WWF urges countries to remember why they are here: humanity and wildlife face an escalating biodiversity crisis that threatens all life on earth. We need to work together to safeguard our one home.”

This article originally appeared in our monthly newsletter, Fieldnotes. Click here to subscribe to future issues.