Where tigers no longer roam

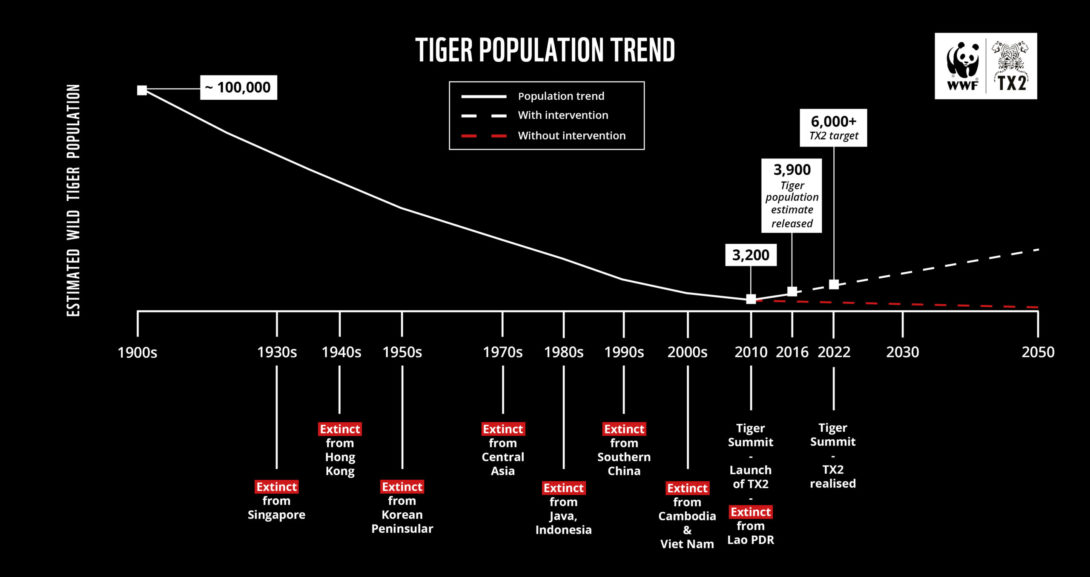

A century ago, tigers could be found across much of Asia but today these big cats occupy as little as 5 per cent of their historic range, which is why WWF launched our Tx2 initiative to double the number of wild tigers between 2010 and 2022, the next Year of the Tiger in the Chinese calendar.

But progress toward this goal has been uneven. While global tiger numbers are on the rise, this majestic cat’s future remains fragile — especially in regions like mainland Southeast Asia where there are now fewer tigers than in 2010.

Why have tigers gone extinct in these places?

Tigers had been declining across Asia for more than 100 years with population extinctions driven by both hunting and habitat loss.

More recently, a Southeast Asian snaring crisis has been emptying forests of their wildlife. Snares are often indiscriminate wire traps that have contributed to the extinction of tigers in Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam and continue to threaten tigers across the region.

In some countries, historical human-tiger conflict was one of the biggest drivers of local tiger extinction, with tigers estimated to have gone extinct in Hong Kong in the 1940s and in Singapore a decade earlier, with the last wild tiger was reportedly killed in Choa Chu Kang Village in 1930.

Although opinions have since changed, tigers were once considered vermin and intentionally hunted with government bounties for kills.

Habitat loss became a threat when the move to industrial agriculture changed the way the world grew food, putting massive areas of land in high demand. In many cases, the land that was cleared was diverse forest which provided prime tiger habitat.

The demand of the illegal wildlife trade has also fueled the extinction of tigers. Wild tigers have been, and still are today, poached for traditional medicine, their skins, and products such as tiger bone wine.

Camera trap image of a tiger in the Dawna Tenasserim landscape of the Tanintharyi Region of Myanmar.

Bringing back the roar

Tigers are in crisis in mainland Southeast Asia. Today only Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar and Thailand have wild tiger populations.

Returning tigers to places where they’ve gone extinct is possible, but only with full support from communities, governments, the private sector, and conservation partners to ensure the reasons for their loss are eliminated.

In Kazakhstan, where tigers were declared extinct 70 years ago, the government, conservation partners and communities are working together to reintroduce tigers to the Central Asian country. If successful, it could mark the first international tiger reintroduction in history, proving it is possible for tigers to return to their historic range.

And countries such as India, Nepal and Russia have also shown that with the right interventions, tiger populations can not only recover, but in some cases, double over a relatively short period of time.

Learn more about WWF’s TX2 Initiative and about WWF-Canada’s efforts to protect big cats in Nepal.